Dear Readers,

What if China’s real “secret weapon” since 1976 wasn’t cheap labor or scale - but an ideological operating system that could rewrite itself without ever admitting a reboot? In today’s featured story, we trace the post-Mao pivot from revolutionary purity to performance legitimacy: how Deng’s black-cat/white-cat pragmatism opened the door to markets, how “socialist market economy” and the “primary stage” narrative made that opening feel Marxist, and how the Party kept the steering wheel even as Shenzhen turned into a laboratory for capitalism-in-a-cage. Then we fast-forward to the age of tech containment—export controls, the chip squeeze, the quiet scramble for compute—and show why energy buildout (coal + renewables + nuclear) and open-weight AI have become strategic counter-moves when hardware gets fenced off. If you want to understand the China of 2025 - the one building infrastructure at scale while shipping models that travel where chips can’t - start here, and keep reading.

All the best,

The ideological contortion: China's socialism

“It doesn't matter if a cat is black or white, if it catches mice it's a good cat (不管黑猫白猫,能捉到老鼠就是好猫).”

— Deng Xiaoping, 1962; 1992

In September 1976, Mao Zedong died - and with him ended an era in which ideology wasn’t just a worldview but a governing technology: a way to organize power, decide who belonged, and define what “progress” meant. The question China faced afterward wasn’t simply who would rule (though that mattered intensely). It was how a revolutionary party could keep its monopoly on authority while escaping the economic stagnation and isolation that threatened the project itself. In the late 1970s, the Communist Party of China (CPC) did something historically unusual: it began dismantling key features of its own command economy without publicly abandoning Marxism-Leninism. The early post-Mao leadership struggle - first under Hua Guofeng, then decisively under Deng Xiaoping - created the political opening for a new logic: pragmatism framed as fidelity. Deng’s famous line: “It doesn’t matter whether a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice,” captured the mood: results would become the new proof of correctness, not its Marxist ideology.

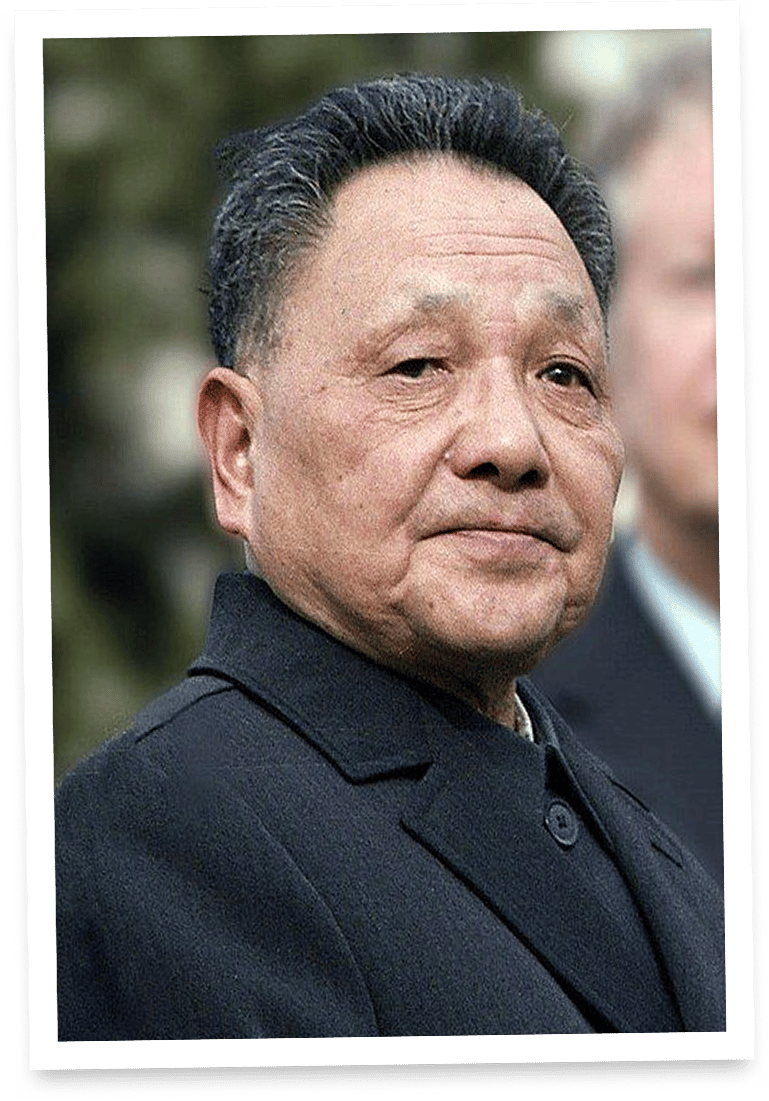

Deng Xiaoping

From that point on, China’s rise can be viewed as a series of controlled experiments: market incentives introduced here, state steering reinforced there; openness to foreign capital, but guarded control over politics; integration into the global economy, but deep investment in strategic autonomy. Over five decades, this approach helped China move from a largely agrarian, inward-looking country into a manufacturing powerhouse and then into a technological contender producing firms like Huawei, Tencent, Alibaba, and Xiaomi; and, more recently, globally influential open-weight AI models.

This metamorphosis is not merely a story of economic growth; it is perhaps the most complex ideological high-wire act in modern history. How did a nation explicitly founded on Marxist-Leninist principles become the world’s factory and a fierce competitor in the hyper-capitalist arena of high tech? How did China re-engineer its political economy after 1976, ideologically and materially, so that market dynamism served state power, and state power accelerated technological ascent, even under escalating U.S.-led restrictions? And more pressingly, how has it managed to withstand a "silicon curtain" of Western embargoes to emerge not just as a survivor, but as a potential architect of the future’s digital infrastructure? To understand the China of 2025, a titan of nuclear energy and AI, we must look back at the moment the script was rewritten.

Subscribe to Superintel+ to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Superintel+ to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Discord Server Access

- Participate in Giveaways

- Saturday Al research Edition Access